How to Take Notes from Books and Lectures

Look at a typical student’s notebook after a lecture.

What you will likely see is a dense, frantic wall of text. The student has spent 50 minutes in a desperate sprint, trying to act as a human stenographer, to capture every word the professor said. They leave the lecture exhausted, with cramped hands and a notebook full of “information.”

And they have understood almost nothing.

This is the central failure of how to take notes. We have been taught, or have assumed, that note-taking is an act of recording. It is not. It is an act of processing.

Your goal in a lecture or while reading a book is not to be a court reporter. It is to be a filter. You are there to dismantle an argument, identify its core components, question them, and then rebuild them in your own mind.

Most note-taking is passive transcription. This is why you forget 80% of it within 24 hours.

This guide will teach you how to stop being a stenographer and start being a thinker. We will cover the two proven, active systems for turning information into knowledge. One is designed for the high-speed, “live” environment of a lecture. The other is designed for the deep, self-paced “dialogue” of reading a book.

The High-Speed Environment

The primary challenge of a lecture is that you cannot control the pace. The professor speaks, and you must keep up. This is where “transcription paralysis” sets in the fear of missing something, which ironically causes you to hear nothing.

The solution is not to write faster. It is to use a system that forces you to listen, filter, and structure information in real-time.

The most effective system ever devised for this is the Cornell Method.

The System: The Cornell Method

Developed by Dr. Walter Pauk at Cornell University in the 1940s, this method is a complete, time-tested “dashboard” for capturing and processing information. It is not just a layout; it is a process.

Its genius is that it forces you to “process” the lecture notes three times, ensuring they move from short-term memory to long-term understanding.

Step 1: The Setup (Before the Lecture)

You cannot use the Cornell Method on the fly. You must prepare your page before the professor says a word.

Take a standard sheet of paper and draw two lines:

-

A Horizontal Line: Draw this about two inches from the bottom of the page. This creates the “Summary Area.”

-

A Vertical Line: Draw this about 2.5 inches from the left edge, starting from the top and stopping at the “Summary Area” line.

You now have three distinct sections:

-

The “Note-Taking Column” (the large, 6-inch column on the right)

-

The “Cue Column” (the narrow, 2.5-inch column on the left)

-

The “Summary Area” (the 2-inch section at the bottom)

This structure is a machine. Now, you are ready to use it.

Step 2: The “Record” Phase (During the Lecture)

You will only write in the large Note-Taking Column on the right.

This is the “capture” phase, but it is not transcription. You must follow a new set of rules. Do not write in full sentences. Full sentences are the enemy of comprehension. They take too long to write, and your brain defaults to “typing” mode instead of “thinking” mode.

Your job is to listen for ideas and capture them as fragments.

-

Use abbreviations.

-

Use bullet points.

-

Use symbols (e.g., “+” for “and,” “->” for “leads to”).

-

Capture key concepts, definitions, examples, and questions the professor poses.

-

Most importantly: Leave white space. Lots of it. Do not cram your notes. Give each idea room to breathe.

You are not creating a perfect transcript. You are creating a “raw material” of ideas that you will process later.

Step 3: The “Reduce” Phase (The 24-Hour Rule)

This is the single most important step in all of note-taking. And it is the one everyone skips.

In the 1880s, psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus (University of Berlin) discovered the “Forgetting Curve.” His research demonstrated that humans forget, on average, 80% of new, passively-learned information within 24 hours.

The Cornell Method is the antidote.

After the lecture that same day, within 24 hours you must sit down with your notes. Look at the “raw material” you captured in the right-hand Note-Taking Column.

Now, look at the empty Cue Column on the left.

Your job is to “reduce” your notes. You will read over the ideas on the right and, in the left-hand column, write down questions that the notes answer.

-

Note on right says: “Mitochondria = powerhouse of the cell. Generates ATP.”

-

Cue on left says: “What is the function of mitochondria?”

-

Note on right says: “Hegemony (Gramsci) = power not just by force, but by consent.”

-

Cue on left says: “How does Gramsci define ‘hegemony’?”

This simple act is the active processing that moves information into your long-term memory. You are forced to re-engage with the ideas, to synthesize them, and to re-frame them as answers to questions. You are turning your passive notes into an active study guide.

Step 4: The “Retain” Phase (The Summary)

After you have filled out the Cue Column, look at the empty Summary Area at the bottom of the page.

Your job is to summarize the entire page in one or two simple sentences. This is the Feynman Technique (named after physicist Richard Feynman) in miniature. If you cannot explain the main idea of the page in your own, simple words, you have not understood it.

This final act of synthesis locks in the knowledge.

Step 5: The “Review” Phase

Your note page is now a perfect, two-way study tool.

-

To Review: Cover the right-hand Note-Taking Column. Use the “Cues” (questions) on the left to quiz yourself.

-

To Study: Read your one-sentence “Summaries” at the bottom of each page to quickly review the entire lecture’s main points.

The Self-Paced Environment

How to take notes from books is a different challenge. The problem is not speed; it is volume and intent.

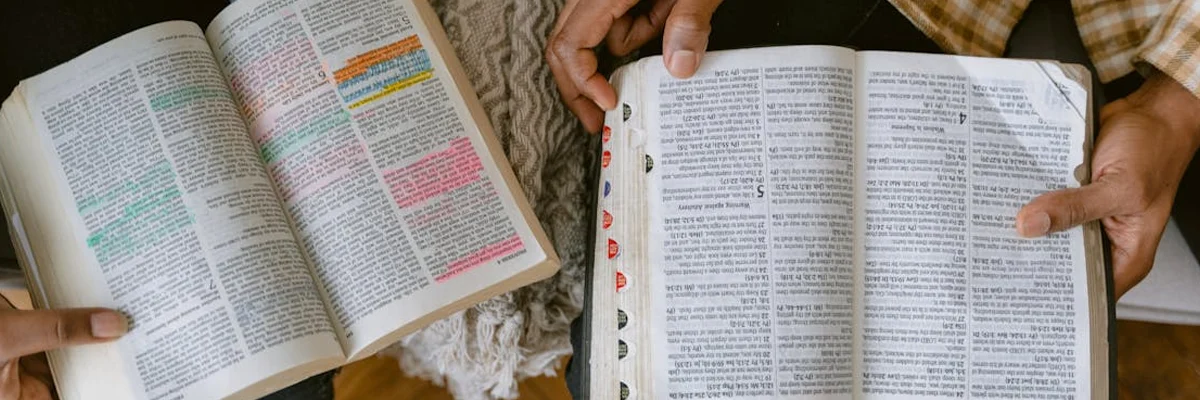

A 400-page book is a mountain. The biggest mistake is “passive highlighting” the “yellow page” disease. A page covered in yellow highlighter is a monument to a reader who was impressed, but who did not think. The second biggest mistake is copying entire quotes into a notebook, which is just transcription by another name.

The goal is not to “collect” quotes. The goal is to build knowledge. You are not reading a book; you are having a dialogue with the author.

The best system for this is an active synthesis method, famously exemplified by the Zettelkasten (or “slip-box”) technique.

The System: The Synthesis Method (aka “Zettelkasten”)

This method, most famously used by sociologist Niklas Luhmann (Bielefeld University) to publish over 70 books, is not about “taking notes.” It is about creating a “second brain.” It is a system for creating a personal, interconnected network of ideas.

Step 1: The “Active Reading” Mindset (The Dialogue)

You must never read a book without a pen in your hand. This is non-negotiable.

You are not a passive receptacle. You are an active participant. Your job is to argue, to question, and to connect. The margins of the book are your “thinking space.”

This brings us to the “1:1 Rule.”

For every passage you underline or bracket, you must write an equal (or greater) amount of your own thoughts in the margin.

Do not just write “This is good.” That is a passive “like.” Write: “Why is this important?” Write: “This contradicts his point in Ch. 2 about X.” Write: “I disagree. He is ignoring the research from Y.” Write: “This is a great example of the ‘confirmation bias’ I read about last week.”

This simple rule forces you to immediately process the information. You are having a live, written dialogue with the author.

Step 2: The “Extraction” (The Zettelkasten Principle)

This is the secret weapon. Do not leave your brilliant ideas inside the book.

A note written in the margin of a book is “dead.” It is trapped. It will be put on a shelf, and you will never see it again. It cannot connect to anything.

The Zettelkasten principle is based on extraction. After you finish a chapter or a book, you go back through your marginalia. You find the big ideas (your own thoughts, or the author’s core concepts).

You then “extract” them onto separate “cards.”

-

This can be a physical index card.

-

This can be a single digital note (in an app like Obsidian, Notion, or Apple Notes).

The Crucial Rule of Extraction: Write the idea in your own words. Do not copy the quote. This is the Feynman Technique again. You must paraphrase it to prove you understand it.

At the bottom of the card/note, you add the reference (e.g., “From: Smith, The Wealth of Nations, p. 45”).

Step 3: The “Network” (Building Your Second Brain)

Now you have a “slip-box” (‘Zettelkasten’) full of atomic, single-idea notes.

Here is the final, brilliant step: You do not file them by book or author.

That is a “library.” It is a dead storage system.

Instead, you file them by topic or idea. And, most importantly, you link them.

When you create a new note, you ask: “What does this connect to?” That note you just wrote on “Hegemony” from Gramsci? You link it to the note you wrote last month on “Power” from Machiavelli’s The Prince.

You are not building a “list” of what you’ve read. You are building a web of what you know.

This system allows for “emergence.” It allows your original ideas to form at the intersection of other people’s ideas. This is how you generate original thought. This is how you prepare for an exam or write a paper. You are not “studying.” You are consulting your own personal, interconnected “second brain.”

Stop Being a Stenographer

The goal is not to have “full” notebooks. The goal is to have an empty head and a full understanding.

Both of these systems Cornell and Synthesis share one core principle. They force you to stop being a passive “recorder.” They force you to be an active processor.

The Cornell Method turns a “live” lecture into a structured, active study guide. The Synthesis Method turns a “static” book into a dynamic, living network of your own ideas.

Stop capturing. Start thinking.

Recommended for you

How to Read Academic Literature Effectively

Reading an academic journal article is not like reading a novel. It is not like reading a blog post. It is a completely different activity. A novel invites you in. A blog post gives you its point quickly. An academic paper, by contrast, is a fortress. It is dense, written in a specialized code, and […]

How to Become More Productive: Step-by-Step Guide

In one afternoon, a small team can draft a long-form article, auto-generate matching social graphics, and cut a 60‑second explainer video—without touching traditional timelines or hiring a studio. The shift isn’t hype: AI tools now turn plain text into publish-ready visuals, videos, and SEO-optimized pages, compressing days of manual work into hours. If your goal […]

Choosing Textbooks for First-Year Students

Becoming a first-year university student involves a series of new, confusing, and often expensive decisions. None is more immediate or frustrating than your first trip to the campus bookstore. You are handed a list of required texts for your five new classes, and the total at the bottom of the receipt could easily fund a […]

Why Classic Literature Remains Relevant

Why do we still read them? This is a question that echoes through classrooms and book clubs. Why do we bother with books written 50, 100, or 200 years ago, by authors who are long dead? The world has changed. We have the internet. We have immediate, global communication. We have new problems, new technologies, […]

Molecular Biology and the Books That Defined It

What is life? For millennia, this question was the domain of priests, philosophers, and poets. It was a question of “spirit,” of a “vital spark,” of a “ghost in the machine.” Then, in the middle of the 20th century, a new group of thinkers took over. They were physicists, chemists, and biologists, and they approached […]

Does Reading Make You Smarter? The Science Behind the Habit

Does reading make you smarter? The simple, reflexive answer is “yes.” It’s a piece of received wisdom we’ve all internalized. We are told to “read more” in the same way we are told to “eat our vegetables.” We know it’s good for us, but the specific reasons remain abstract. What does “smarter” even mean? If […]

What Is Reading Fluency and How to Improve It

Ask someone what is reading fluency, and they will likely give you a simple answer: “It means reading fast.” This answer is understandable. It is intuitive. But it is also dangerously incomplete. Reading fluency is not a race. It is not about simply processing words at maximum velocity. True fluency is a complex skill, a […]

How to Publish a Book: A Step-by-Step Guide for New Authors

For every new author, the dream is the same. It is the moment of holding a finished, physical book in your hands. It is the smell of the paper, the weight of the object, the sight of your name on the cover. It is a dream of validation and completion. But between the final period […]