Must-Read Books on Politics and Society

Why does the world feel so chaotic?

We watch the daily news and see a storm of seemingly random, disconnected events. A financial market crashes. A new law is passed. A war breaks out. A populist leader rises. A corporation makes a decision that affects millions.

We treat these events as “news.” As discrete happenings. We argue about the personalities involved, the “good guys” and the “bad guys.”

But what if it isn’t chaos? What if we are not watching a storm, but a machine?

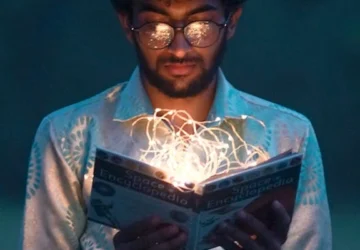

The greatest and most must-read books on politics and society are not those that just report the events. They are the ones that give us the “source code.” They reveal the hidden systems, the underlying logic, and the invisible “matrices” that govern our behavior, often without our conscious consent.

These books are dangerous. They are “red pills.” They are not about “what happened last year.” They are about why things keep happening in the same way, over and over, for centuries.

If you truly want to understand the world, you must stop looking at the surface and start looking for the systems underneath. The following four books are essential manuals to four of the most powerful “systems” that run our lives: the system of power, the system of money, the system of resistance, and the system of myth.

The System of Power: “The Prince” (Niccolò Machiavelli, 1532)

No book on politics has been more influential, or more misunderstood, than “The Prince.” People hear the word “Machiavellian” and think of pure, cartoonish evil. They think of manipulation and backstabbing.

They are not wrong. But they are missing the point.

“The Prince” is not a work of philosophy. It is not a moral debate. It is a technical manual. It is a cold, terrifyingly precise instruction booklet on how power actually works.

The “System” It Reveals: Before Machiavelli, books about leadership were “mirrors for princes.” They were moral guides, arguing that a prince must be pious, just, kind, and merciful. They described how a leader should be.

Machiavelli, writing after being tortured and exiled, had no patience for this. He decided to write about how leaders actually are.

He reveals a system that is completely divorced from Christian morality. In Machiavelli’s system, “good” and “bad” are irrelevant. There is only one metric: the acquisition and maintenance of power (or “the state”).

The book is a manual for a new ruler on how to consolidate his control. Machiavelli’s advice is purely mechanical. He introduces the concepts of Virtù (not “virtue,” but strength, skill, and masculine will) and Fortuna (luck, or the chaotic nature of the world). A good prince does not rely on Fortuna. He uses his Virtù to “master” her, to bend the chaos of the world to his will.

His most famous chapter asks: “Is it better to be loved or feared?”

Machiavelli’s answer is a perfect example of his “system.” It would be best to be both. But since that is difficult, “it is much safer to be feared than loved.” Why? Because love is fickle, based on the whims of the people. Fear, however, is constant. It is based on the prince’s credible, consistent threat of punishment. The prince controls fear. He does not control love.

Therefore, he must choose fear.

Why It Is a Must-Read: “The Prince” is the source code for all modern power politics. It is the first book to treat power as a science rather than a divinity.

When you watch a politician “pivot” on an issue, or use a “wedge” issue to divide opponents, or say one thing in public while doing another in private, that is not a moral failure. That is a Machiavellian calculation.

This book reveals the hidden operating system that runs beneath the “public-facing” system of morality. It shows that the goal of a political actor is not to be “good.” The goal is to win. It is a terrifying, essential, and brutally honest book.

The System of Economics: “Capital” (Vol. 1) (Karl Marx, 1867)

If “The Prince” reveals the hidden mechanics of political power, Karl Marx’s “Capital” reveals the hidden mechanics of economic power.

This is another book most people “know” but have never read. They mistake it for the “Communist Manifesto.” But “Capital” is not a short, fiery pamphlet. It is a vast, dense, 1,000-page scientific critique of a system.

It is, in short, the instruction manual for Capitalism.

The “System” It Reveals: Marx’s core argument is that our lives, laws, religions, and social structures are not the product of “ideas.” They are the product of our economic system. The “system” of Capitalism, he argues, is a vast, invisible force with its own logic, and it is in charge, not us.

He reveals a hidden world. We think we are just “going to work” and “buying things.” Marx shows us what is happening “under the hood.”

-

Commodity Fetishism: This is his most brilliant idea. We think we are just exchanging objects. (I give you $5, you give me coffee). Marx says no. Under Capitalism, the commodities are the ones in a relationship, and we (the humans) are just their puppets. We have imbued inanimate objects with a social, almost “magical” power that now dominates our lives.

-

Surplus Value: Where does profit come from? Marx says it is theft. He argues that a worker is paid for (for example) 8 hours of work. But in the first 4 hours, the worker creates enough value to cover their own wages. The “surplus value” created in the next 4 hours is unpaid labor, and that is what the capitalist takes as “profit.” This extraction, he argues, is the hidden, exploitative engine of the entire system.

-

Alienation: Because of this, the worker becomes “alienated” (a stranger) from their own work, from the product they create, from their fellow workers, and, ultimately, from themselves.

Why It Is a Must-Read: “Capital” is the “source code” for modernity. You do not have to be a “Marxist” to read it. You read it to understand the system you live in.

It is the book that explains why you feel “burnt out” (you are alienated from your labor). It explains why corporations seem to have a logic of their own, obsessed with endless growth, often at the expense of human or environmental well-being (the system demands the constant extraction of surplus value). It reveals that the “free market” is not just a place of opportunity; it is a relentless system of logic that shapes our very lives.

The System of Resistance: “The Art of Not Being Governed” (James C. Scott, 2009)

The first two books are about the systems that control us. This book is about the systems we use to escape.

It is one of the most important history books of the 21st century because it flips our entire understanding of “civilization” on its head.

The “System” It Reveals: For 3,000 years, “history” has been written by the states. We are taught a simple story: humanity started as “primitive” hunter-gatherers, “evolved” into sedentary, grain-growing states (like in Egypt or Mesopotamia), and this was the “dawn of civilization.”

James C. Scott’s mind-blowing thesis is: What if this is a lie? What if “civilization” (the grain-state) was actually a trap?

He argues that the state was, for most of history, a “machine” for capturing people. Its purpose was to collect taxes, conscript soldiers, and force labor. And for 3,000 years, vast populations of “barbarians” were not “primitive.” They were refugees. They were people who had deliberately fled the state.

Scott reveals the “system of state evasion.” He focuses on “Zomia,” a vast, highland region in Southeast Asia (and other “shatter zones” around the world).

-

Geography as a Political Choice: People did not live in the inaccessible mountains because they were “backward.” They lived there on purpose. The mountains were a political choice. The difficult terrain made it impossible for the state’s armies and tax collectors to reach them.

-

State-Evading Crops: Why did these “hill people” prefer illegible crops? Grain (like rice or wheat) is the perfect state crop: it ripens all at once, it is harvested in the open, and it is easily measured and taxed. The hill people, instead, grew yams or cassava. These crops are “illegible.” They can be hidden in the ground, harvested any time, and are impossible for a tax collector to find or measure.

-

Flexible Cultures: These societies deliberately avoided “kings” and “writing” because those are the tools of the state. They chose flexible, mobile social structures that made them “ungovernable.”

Why It Is a Must-Read: This book completely re-frames must-read books on society. It gives us a new respect for the “barbarians.” It argues that our history is not a simple line “up” to civilization. It is a long, complex story of people fighting for freedom against the state. It reveals the hidden, 3,000-year history of human resistance, written not in documents, but in the landscape itself.

The System of Myth: “Sapiens” (Yuval Noah Harari, 2011)

If the first three books reveal the source code for power, economics, and resistance, this book reveals the “source code” for humanity itself.

Harari’s book is a “brief history of humankind” that asks one simple, devastating question: How did Homo sapiens, a fairly unimpressive ape, conquer the entire planet?

The “System” It Reveals: The answer is not our “opposable thumbs” or our “big brains.” The answer, Harari argues, is our imagination.

Harari’s central thesis is that Sapiens conquered the world because we are the only animal that can cooperate flexibly in large numbers. And we do this because of one unique skill: our ability to create, believe in, and live inside “shared fictions.”

These are “intersubjective realities”: things that are not objectively real (like a rock) and are not just subjectively real (like my imaginary friend), but exist in the shared consciousness of millions.

-

Money: The ultimate fiction. We all agree that this green piece of paper (or, even more absurdly, a “1” and a “0” in a bank’s computer) has value. A chimpanzee cannot be trained to do this.

-

Nations: A nation is just a story. It is a line on a map. But we believe in “America” or “France” so strongly that we are willing to die for that “fiction.”

-

Corporations: What is “Google”? You can’t touch it. It is not its buildings (it can sell them). It is not its employees (they can be fired). “Google” is a legal fiction that we all agree “exists” and can “own” things.

-

Human Rights: A “right” is not a physical object. It is a powerful, “self-evident” story that we have collectively agreed to believe in.

Why It Is a Must-Read: “Sapiens” is the “source code” for all the other “source codes.”

It reveals that the “state” that Machiavelli serves, the “Capital” that Marx critiques, and the “civilization” that Scott’s subjects flee are all just stories. They are powerful, world-changing “myths” that we invented.

This book is the ultimate “matrix” reveal. It shows us that we are living in a world not of things, but of stories. This is our superpower. It is what allows us to build cities and go to the moon. It is also, as Harari shows, what allows us to create horrific wars, ecological destruction, and systemic inequality.

The Manuals for Our Machine

These four must-read books on politics and society are not just “books.” They are lenses.

They are tools for seeing the world as it is, not as we wish it were.

“The Prince” reveals the raw, amoral code of power. “Capital” reveals the relentless, invisible code of economics. “The Art of Not Being Governed” reveals the defiant, geographic code of resistance. And “Sapiens” reveals the foundational, fictional code of human cooperation itself.

To read them is to stop being a passive “user” of these systems. It is to become a “programmer.”

You stop seeing chaos. You start seeing the machine. And for the first time, you can begin to understand how it actually works.

Recommended for you

Sci-Fi vs Fantasy: Key Differences and What to Read

On the surface, the difference seems simple. One genre has spaceships and aliens. The other has dragons and elves. Science Fiction, we are told, is about the future, and Fantasy is about the past. This is a shallow analysis. And it is wrong. This “aesthetic” definition one of props and settings collapses immediately under any […]

Books Every Student Should Read Before University

University is not just the next step after school. It is a fundamentally different kind of intellectual environment. High school often rewards memorization and acceptance of authority. University, at its best, rewards questioning. It is not just about learning what to think; it is about learning how to think. It is about engaging with complex, […]

How to Take Notes from Books and Lectures

Look at a typical student’s notebook after a lecture. What you will likely see is a dense, frantic wall of text. The student has spent 50 minutes in a desperate sprint, trying to act as a human stenographer, to capture every word the professor said. They leave the lecture exhausted, with cramped hands and a […]

Does Reading Make You Smarter? The Science Behind the Habit

Does reading make you smarter? The simple, reflexive answer is “yes.” It’s a piece of received wisdom we’ve all internalized. We are told to “read more” in the same way we are told to “eat our vegetables.” We know it’s good for us, but the specific reasons remain abstract. What does “smarter” even mean? If […]

How to Read Academic Literature Effectively

Reading an academic journal article is not like reading a novel. It is not like reading a blog post. It is a completely different activity. A novel invites you in. A blog post gives you its point quickly. An academic paper, by contrast, is a fortress. It is dense, written in a specialized code, and […]

Why Classic Literature Remains Relevant

Why do we still read them? This is a question that echoes through classrooms and book clubs. Why do we bother with books written 50, 100, or 200 years ago, by authors who are long dead? The world has changed. We have the internet. We have immediate, global communication. We have new problems, new technologies, […]

Best Biographies of Influential Figures

What makes a biography “great”? The simple answer is “accuracy.” A good biography, we assume, is one that gets all the facts right. It has the correct dates, the verified quotes, the detailed footnotes. This answer is true, but it is incomplete. It is the answer for a historian, not a reader. A simple collection […]

How Fiction Can Support Learning and Imagination

For centuries, a persistent myth has haunted our perception of reading. It is the myth of the “serious” versus the “frivolous.” In this binary, non-fiction is the “serious” stuff. It is the realm of facts, history, science, and learning. Fiction, on the other hand, is cast as the “frivolous” sibling. It is entertainment. It is […]